Dear friend,

It’s been a season of grief, personally and collectively. Some days, I have felt flattened, incapacitated by it; other days, I am able to gather myself and take a few wobbly steps through the haze. I’ve been trying to come to terms with life’s tragedies: the casual cruelty in the way we often engage with each other, the persistence of atrocities around the world, the violations of human dignity in the margins of society, the ordinary devastation of losing people we love. All I can say is: I wish we could learn to be better, kinder, gentler — to each other, to ourselves, to the world.

To live in this world, it often feels like we are forced to lobotomize ourselves. There is no space in our lives to collapse under the weight of grief, so we must shut ourselves down from within. We become numb and detached, entering a state of self-protective apathy until the next tragedy shatters this fragile armor — again, and again, and again.

Remaining tender and open despite the world’s harshness is a brave and beautiful act. So often, sensitivity is mistaken for weakness, and avoidance of our own terror and grief is painted as stoicism. We cannot carry on with our lives while ignoring the cries of the heart, else we risk it fossilizing. The great tasks that lie ahead of us — to collectively reimagine and reinvent our world — require the ability to feel deeply and remain intact, to acknowledge and endure the tragedies of our time without falling into despair.

I think of Albert Camus’ essay, “The Almond Trees,” in which he writes that we cannot succumb to what Nietzsche called the spirit of heaviness. Instead, we must find the space in our minds “where courage and contemplation can live in harmony” and refuse to wallow in misery:

“Let us not listen too much to those who proclaim that the world is at an end. Civilizations do not die so easily, and even if our world were to collapse, it would not have been the first. It is indeed true that we live in tragic times. But too many people confuse tragedy with despair.”

Writing in the early days of World War II, Camus urges us undertake the endless task of reducing the contradictions of human condition:

“Our task as [humans] is to find the few principles that will calm the infinite anguish of free souls. We must mend what has been torn apart, make justice imaginable again in a world so obviously unjust, give happiness a meaning once more to peoples poisoned by the misery of the century. Naturally, it is a superhuman task. But superhuman is the term for tasks [we] take a long time to accomplish, that’s all.”

Doing so, he tells us, requires a quiet fortitude:

“Before the vastness of the undertaking, let no one forget strength of character. I don’t mean the theatrical kind on political platforms, complete with frowns and threatening gestures. But the kind that through the virtue of its purity and its sap, stands up to all the winds that blow in from the sea. Such is the strength of character that in winter of the world will prepare the fruit.”

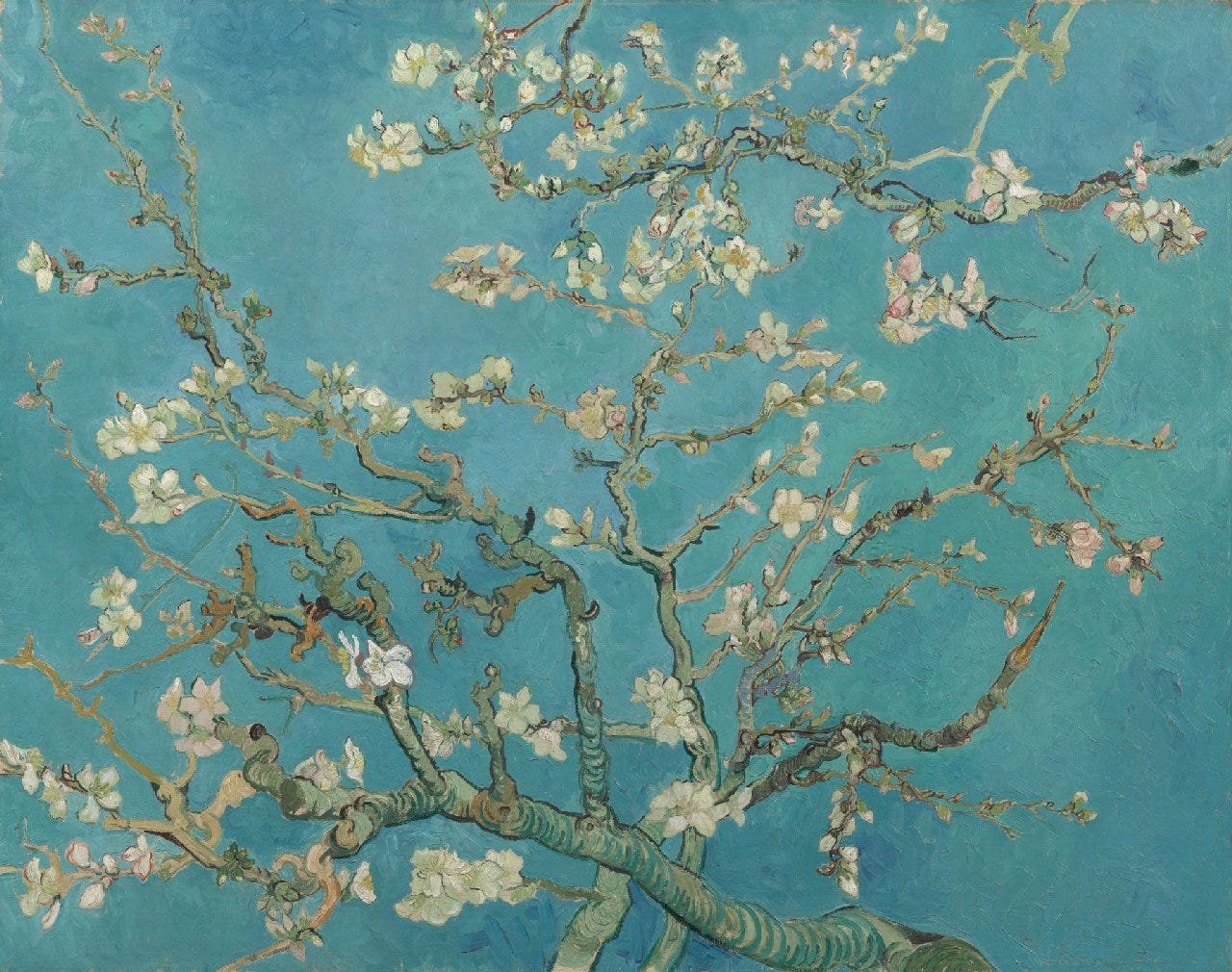

Every winter in Algiers, Camus would wait for the almond trees outside his window to blossom. When they finally, suddenly did in the course of “one cold, pure February night,” he would marvel at “the sight of this fragile snow resisting the rains and the wind from the sea.” Like the almond trees, Camus finds that even “in the depths of winter, I finally learned that within me there lay an invincible summer.”

May we all find the invincible summer within, and harness its strength to resist the wind and the rain of our turbulent times so that we may blossom.

With love,

Ash

(P.S. I’m hosting a salon on flourishing in times of darkness on Oct. 25, 6-8 p.m. PT. I’d love for you to join. If the ticket price presents an obstacle, please email me at ashleydzhang@gmail.com 🤍)

What a wonderful cascade of hope just poured over me. Thank you for sharing

This was fantastic!

Such a wonderful summation of some of Camus’s writing. Thank you